Grenfell Tower fire1

Nobody can react to the Grenfell Tower fire with anything other than horror, sadness, anger and resolve.

Much of that anger is, legitimately, directed at the elite professions who make the decisions on which individual safety turns. I am proud to have been a member of two elite professions during my lifetime: engineering and law. I wanted to say something about the nature of practice, of responsibility and of blame.

It is too early to be confident of causes, remedies or punishments. Those will have to await full investigation but professionals of all disciplines will need little encouragement to spend the coming weeks searching their own souls over their wider obligations to society. For, that is what membership of a profession entails.

The need for bureaucracy

“Bureaucracy” is a word most often used pejoratively, as a rebuke to a turgid rigidity that frustrates spontaneity, creativity, efficiency and expedition. It is that. But once society starts to enjoy systems of reasonable complexity, civil aviation, networked electricity supply, international transport of goods etc., much decision making is going to be reserved to a cadre of experts. Diane Vaughan’s analysis of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster2 is a relevant and salutary account of engineering as a bureaucratic profession.

Of course, you can embed some of your bureaucracy in software but don’t expect that to improve spontaneity, creativity or flexibility. Efficiency and expedition, perhaps. Even putting a bunch of flowers on your dining table requires this.

I have often, on this blog, cited Robert Michels’ iron law of oligarchy. Michels contended that any team of bureaucrats soon realised the power they held in controlling the levers of policy. A willingness to pull those levers in the direction of their own self-interest, and a jealous protection of their professional status and expertise, soon followed. That sometimes put them at odds with the objectives they were supposed to be implementing on behalf of their principals. As one political scientist put it:3

Many governance dysfunctions arise because the agents have different agendas from the principals, and the problem of institutional design is related to incentivising the agents to do the principal’s bidding.

Max Weber had realised all this earlier in the nineteenth century. Weber was a child of that mother of all bureaucracies, the Prussian civil service. The self interest of managing elites bothered him and he sought to inculcate an ethic of responsibility whereby professionals thought hard about the wider consequences of their decisions.4 That is the ethic that modern professions seek to foster among their members. Engagement in a profession carries responsibilities.

Faith in regulation

So much marginally informed debate among journalists has been about “the building regulations”. I guess that they mean the Building Regulations 2010. You can examine the relevant parts here, for what they are worth. Scroll down to Part B. Of course the Regulations themselves are supported by the statutory guidance. Here that is. The guidance refers to a legion of British Standards. As I learned during my time in the railway industry, the scientific basis of the guidance is not always easy to trace. Expect to hear more of that as inquiries progress.

The fundamental truth of such regulations is that it is the building professionals themselves who write them. Who else? That does not mean that the professionals, even in conclave, are infallible. Nobel laureate psychologist Daniel Kahneman has written extensively about the bounded rationality that limits everybody’s individual, or group, vision beyond a limited range of experiences, values and prejudices. Experts are just as prone as anybody. You and me too.5 It is unlikely that software will do a better job. Expert systems will work, here I go again, in “an environment that is sufficiently regular to be predictable”. I heard Daniel Dennett speak in London recently. Software will provide us with tissues not colleagues.

All this feeds into the collateral phenomenon whereby businesses actively use their expert involvement in setting regulations as a strategy to capture market share, promote their own products and erect barriers against entry for would-be competitors. The extreme consequence here is regulator capture, where the regulator becomes so dependent upon the expertise of the regulated that she is glad to let them define the regulatory regime.

To some extent, the self validating nature of expertise is reinforced, at least in the UK, by the approach of the courts. In assessing the negligence of a professional an individual is judged against the standards of his profession. Only where no reasonable member of his profession would have acted as he did is he negligent.6, 7 But the courts have warned that, in some circumstances, they might call into question the standards of a whole profession if there were a failure of logic. That is something that the courts would never do lightly.8 It would be a spectacle indeed.

When it comes to professional responsibility, the courts refuse to be dazzled by statutory regulations or industry standards. Professionals are expected to exercise their judgment and not hide behind mere compliance.9 In 2003, giving judgment against a firm of architects for inadequate fire precautions in a food factory refurbishment, Judge Bowsher QC observed:10

I should add that I was not the slightest impressed by the submission that since the defendants had complied with their statutory requirements … they had fully performed their duties.

This is what a judge said in a different case concerning the safety of a flight of stairs.11

Looking at a photograph of the stairs, I myself would form the view that they are reasonably safe … But it is the fact that the stairs did not comply with the Building Regulations, or the relevant British Standard. That is evidence which we must certainly take into account. It represents the current professional opinion as to what is desirable in order that accidents should be avoided. But it is one thing to lay down regulations and standards, with that objective, and another to define what is reasonably safe in the circumstances of a particular case [emphasis added].

In any event, trying to manage a risk by statutory regulation is not so efficient a means as you might think. Regulations do not always ensure the best outcome for society.12

Trust in elites

That all leaves the elite professions with grave responsibilities. Let none of us deny that another salient feature of the professions is that they are businesses run to make a profit for the professionals. Members get the further reward of status in society. I know that we have all constructed narratives of our own expertise and that challenges, particularly from clients, are not always welcome. We think we know best and we don’t always want to waste the client’s time explaining what to us seems so obvious.

And when things go wrong, and they will, all that is thrown back at us. Quite justifiably. Trust in bureaucracy has been a recurrent theme on this blog. It is a complex matter. When it leads to herd immunity from disease it is good. When it leads to complicity in torture it is bad. The public trust we aspire to is not blind faith. It is collaboration. Blind faith leads to bad consequences, collaboration to an environment where professionals are able to explain and reassure. Reflecting on that, I think there are some things was all can do to improve that relationship of trust.

Listen The most useful person on a project is often the person who knows nothing about it. She can ask the dumb question. Physicists told Gulgielmo Marconi he would not be able to transmit a radio signal across the Atlantic. But he did, not because he knew something the physicists didn’t but because sometimes it takes an unashamed maverick to test an orthodoxy.13 There are sundry examples of rumours and folk tales that have sparked scientific curiosity and discovery. Sometimes data is the plural of anecdote. It’s not even all about testing scientific theories. People sometimes need confidence and reassurance in unfamiliar situations. They need to be told, in language they understand, what is happening and why you think this is a good idea. Their questions and reservations need to be taken seriously.

A signal is a signal One of the key skills for any professional is being able to distinguish signal from noise. Where there is a signal, a surprise, that suggests an established orthodoxy has stopped working then you must immediately take action to protect those at risk. The “regular environment” you relied on is blown. Don’t wait to see if it happens again. Don’t dismiss it as a “one off” or, heaven forbid, the most useless word in the English language, an “outlier”. It is the signals that contain all the information. Don’t relax when the signal isn’t repeated immediately. That is just regression to the mean. It’s what signals do. Something that you didn’t expect has happened. Pierce the veil of bounded rationality. Protect the client, investigate and look to update your practice.

Noise is noise The corollary to taking signals seriously is not mistaking noise for signal. When that happens we start looking for causes specific of an individual outcome when the true causes were generic to all outcomes. Professionals also need to know when they are embedded in a “stable system of trouble”. That brings its own challenges, not least of which is the cost and effort of perpetually protecting the client.

Humility Professionals don’t always get it right. There are individual errors. There are systemic failures of practice. If you have to start hiding behind the shield that you are beyond challenge and that dissenting views are outlawed then you are probably dismissing the best hope you have for avoiding problems.

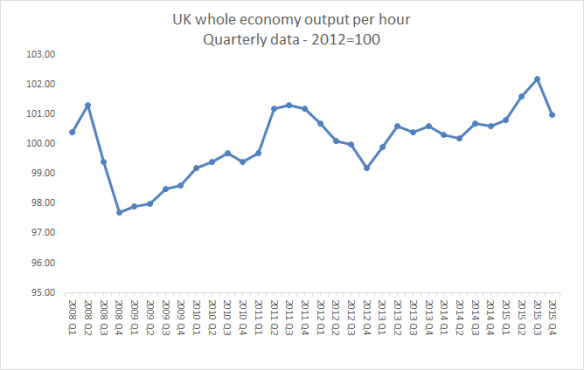

Continual improvement We have to keep listening to counsels of despair from politicians about productivity. It is down to us. Continual improvement is not just for our individual domain expertise, it’s also about getting better at listening, distinguishing signal from noise and practising humility. It’s about getting better at improving too.

Professionals have bodies to kick and souls to damn

Over two hundred years ago, English judge Edward Thurlow famously observed that corporations have neither bodies to kick nor souls to damn. I am always baffled by calls, in cases like that of Grenfell Tower, for prosecutions for corporate manslaughter. The calls seem to reflect a mistaken sentiment that corporate manslaughter is some sort of aggravated form of manslaughter. This isn’t just manslaughter, it’s corporate manslaughter. But why would anybody want to relieve individuals of responsibility and impose it on a faceless abstraction?

Part of the deal when seeking certification as a professional is that you assume a responsibility to society. That’s where you get your status from. When you fail you will be held to account. There are always voices calling for an end to blame culture. But have no doubt, it is a professional’s duty to act within the standards she has adopted. If she falls below those standards then reparation is expected, to the extent that it remains possible. Anybody who causes death when they fall sufficiently far below standard can expect to be indicted for manslaughter and, on conviction, punished and shamed. There is a principle in criminal law called fair labelling. The name of a crime must reflect the offence. Manslaughter is a fair label in such cases.

There has been an increasing tendency in the UK for legislators to take power to order reparation away from the civil courts and to attempt to regulate with criminal sanctions. I am not persuaded that is always the right approach.

Trust in elites, bureaucrats, experts, call them what you will, is important. South African statesman Paul Kruger once remarked:

When I look at history I’m a pessimist. When I look at pre-history I’m an optimist.

If you live in the UK then, on any measure you can dream up, life is getting safer and better. That is the triumph of elite engineers, planners, security professionals, physicians … I could go on. If people at large lose faith in professionals then it will be to our common ruin. Only the professionals can work on building the trust we need. Politicians won’t do it.

What did you do today?

References

- Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Grenfell Tower fire (wider view).jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php title=File:Grenfell_Tower_fire_(wider_view).jpg&oldid=248417865 (accessed June 25, 2017)

- Vaughan, D (1996) The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture, and Deviance at NASA, University Of Chicago Press

- Fukuyama, F (2012) The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution, Profile Books, p207

- Kim, Sung Ho, “Max Weber”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2012 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Kahneman, D (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow, Allen Lane, pp199-254

- Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 WLR 582

- Pantelli Associates Ltd v Corporate City Developments Number Two Ltd [2010] EWHC 3189 (TCC)

- Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority [1996] 4 All ER 771

- Charlesworth & Percy on Negligence, 12th ed., 2010 and supplements, 7-46

- Sahib Foods Ltd & Ors v Paskin Kyriakides Sands (A Firm) [2003] EWHC 142 (TCC) at [43]

- Green v Building Scene Limited [1994] PIQR P259, CA at 269

- Coase, R H (1960) “The problem of social cost” Journal of Law and Economics 3, 1-44

- Raboy, M (2016) Marconi: The Man Who Networked the World, Oxford, p176

Holmes is also correct that disappointment is, in itself, no reason to change plan. What she neglects is that there is a phenomenon that does legitimately invite change: a surprise. It is a surprise that alerts us to an inconsistency between the real world and our design. A surprise ought to make us go back to our working business plan and examine the assumptions against the real world data. A switch to Plan B is not inevitable. There may be other means of mitigation: Act, Adapt or Abandon. The surprise could even be an opportunity to be grasped. The Plan B doesn’t have to be negative.

Holmes is also correct that disappointment is, in itself, no reason to change plan. What she neglects is that there is a phenomenon that does legitimately invite change: a surprise. It is a surprise that alerts us to an inconsistency between the real world and our design. A surprise ought to make us go back to our working business plan and examine the assumptions against the real world data. A switch to Plan B is not inevitable. There may be other means of mitigation: Act, Adapt or Abandon. The surprise could even be an opportunity to be grasped. The Plan B doesn’t have to be negative.

Smart investigators know that the provenance, reliability and quality of data cannot be taken for granted but must be subject to appropriate scrutiny. The modern science of

Smart investigators know that the provenance, reliability and quality of data cannot be taken for granted but must be subject to appropriate scrutiny. The modern science of