In 1911, Robert Michels embarked on one of the earliest investigations into organisational culture. Michels was a pioneering sociologist, a student of Max Weber. In his book Political Parties he aggregated evidence about a range of trade unions and political groups, in particular the German Social Democratic Party.

In 1911, Robert Michels embarked on one of the earliest investigations into organisational culture. Michels was a pioneering sociologist, a student of Max Weber. In his book Political Parties he aggregated evidence about a range of trade unions and political groups, in particular the German Social Democratic Party.

He concluded that, as organisations become larger and more complex, a bureaucracy inevitably forms to take, co-ordinate and optimise decisions. It is the most straightforward way of creating alignment in decision making and unified direction of purpose and policy. Decision taking power ends up in the hands of a few bureaucrats and they increasingly use such power to further their own interests, isolating themselves from the rest of the organisation to protect their privilege. Michels called this the Iron Law of Oligarchy.

These are very difficult matters to capture quantitavely and Michels’ limited evidential sampling frame has more of the feel of anecdote than data. “Iron Law” surely takes the matter too far. However, when we look at the allegations concerning misconduct within FIFA it is tempting to feel that Michels’ theory is validated, or at least has gathered another anecdote to take the evidence base closer to data.

But beyond that, what Michels surely identifies is a danger that a bureaucracy, a management cadre, can successfully isolate itself from superior and inferior strata in an organisation, limiting the mobility of business data and fostering their own ease. The legitimate objectives of the organisation suffer.

Michels failed to identify a realistic solution, being seduced by the easy, but misguided, certainties of fascism. However, I think that a rigorous approach to the use of data can guard against some abuses without compromising human rights.

Oligarchs love traffic lights

I remember hearing the story of a CEO newly installed in a mature organisation. His direct reports had instituted a “traffic light” system to report status to the weekly management meeting. A green light meant all was well. An amber light meant that some intervention was needed. A red light signalled that threats to the company’s goals had emerged. At his first meeting, the CEO found that nearly all “lights” were green, with a few amber. The new CEO perceived an opportunity to assert his authority and show his analytical skills. He insisted that could not be so. There must be more problems and he demanded that the next meeting be an opportunity for honesty and confronting reality.

I remember hearing the story of a CEO newly installed in a mature organisation. His direct reports had instituted a “traffic light” system to report status to the weekly management meeting. A green light meant all was well. An amber light meant that some intervention was needed. A red light signalled that threats to the company’s goals had emerged. At his first meeting, the CEO found that nearly all “lights” were green, with a few amber. The new CEO perceived an opportunity to assert his authority and show his analytical skills. He insisted that could not be so. There must be more problems and he demanded that the next meeting be an opportunity for honesty and confronting reality.

At the next meeting there was a kaleidoscope of red, amber and green “lights”. Of course, it turned out that the managers had flagged as red the things that were either actually fine or could be remedied quickly. They could then report green at the following meeting. Real career limiting problems were hidden behind green lights. The direct reports certainly didn’t want those exposed.

Openness and accountability

I’ve quoted Nobel laureate economist Kenneth Arrow before.

… a manager is an information channel of decidedly limited capacity.

Essays in the Theory of Risk-Bearing

Perhaps the fundamental problem of organisational design is how to enable communication of information so that:

- Individual managers are not overloaded.

- Confidence in the reliable satisfaction of process and organisational goals is shared.

- Systemic shortfalls in process capability are transparent to the managers responsible, and their managers.

- Leading indicators yield early warnings of threats to the system.

- Agile responses to market opportunities are catalysed.

- Governance functions can exploit the borrowing strength of diverse data sources to identify misreporting and misconduct.

All that requires using analytics to distinguish between signal and noise. Traffic lights offer a lousy system of intra-organisational analytics. Traffic light systems leave it up to the individual manager to decide what is “signal” and what “noise”. Nobel laureate psychologist Daniel Kahneman has studied how easily managers are confused and misled in subjective attempts to separate signal and noise. It is dangerous to think that What you see is all there is. Traffic lights offer a motley cloak to an oligarch wishing to shield his sphere of responsibility from scrutiny.

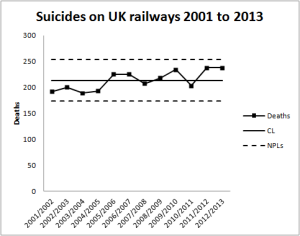

The answer is trenchant and candid criticism of historical data. That’s the only data you have. A rigorous system of goal deployment and mature use of process behaviour charts delivers a potent stimulus to reluctant data sharers. Process behaviour charts capture the development of process performance over time, for better or for worse. They challenge the current reality of performance through the Voice of the Customer. They capture a shared heuristic for characterising variation as signal or noise.

Individual managers may well prefer to interpret the chart with various competing narratives. The message of the data, the Voice of the Process, will not always be unambiguous. But collaborative sharing of data compels an organisation to address its structural and people issues. Shared data generation and investigation encourage an organisation to find practical ways of fostering team work, enabling problem solving and motivating participation. It is the data that can support the organic emergence of a shared organisational narrative that adds further value to the data and how it is used and developed. None of these organisational and people matters have generalised solutions but a proper focus on data drives an organisation to find practical strategies that work within their own context. And to test the effectiveness of those strategies.

Every week the press discloses allegations of hidden or fabricated assets, repudiated valuations, fraud, misfeasance, regulators blindsided, creative reporting, anti-competitive behaviour, abused human rights and freedoms.

Where a proper system of intra-organisational analytics is absent, you constantly have to ask yourself whether you have another FIFA on your hands. The FIFA allegations may be true or false but that they can be made surely betrays an absence of effective governance.

#oligarchslovetrafficlights

A supposed corollary to the

A supposed corollary to the

The UK’s Passport Office is in difficulties. They have a

The UK’s Passport Office is in difficulties. They have a