W Edwards Deming was very impressed with Japanese railways. In Out of the Crisis (1986) he wrote this.

The economy of a single plan that will work is obvious. As an example, may I cite a proposed itinerary in Japan:

1725 h Leave Taku City. 1923 h Arrive Hakata. Change trains. 1924 h Leave Hakata [for Osaka, at 210 km/hr] Only one minute to change trains? You don’t need a whole minute. You will have 30 seconds left over. No alternate plan was necessary.

My friend Bob King … while in Japan in November 1983 received these instructions to reach by train a company that he was to visit.

0903 h Board the train. Pay no attention to trains at 0858, 0901. 0957 h Off. No further instruction was needed.

Deming seemed to assume that these outcomes were delivered by a capable and, moreover, stable system. That may well have been the case in 1983. However, by 2005 matters had drifted.

The other night I watched, recorded from the BBC, the documentary Brakeless: Why Trains Crash about the Amagasaki rail crash on 25 April 2005. I fear that it is no longer available in BBC iPlayer. However, most of the documentaries in this BBC Storyville strand are independently produced and usually have some limited theatrical release or are available elsewhere. I now see that the documentary is available here on Dailymotion.

The other night I watched, recorded from the BBC, the documentary Brakeless: Why Trains Crash about the Amagasaki rail crash on 25 April 2005. I fear that it is no longer available in BBC iPlayer. However, most of the documentaries in this BBC Storyville strand are independently produced and usually have some limited theatrical release or are available elsewhere. I now see that the documentary is available here on Dailymotion.

The documentary painted a system of “discipline” on the railway where drivers were held directly responsible for outcomes, overridingly punctuality. This was not a documentary aimed at engineers but the first thing missing for me was any risk assessment of the way the railway was run. Perhaps it was there but it is difficult to see what thought process would lead to a failure to mitigate the risks of production pressures.

However, beyond that, for me the documentary raised some important issues of process discipline. We must be very careful when we make anyone working within a process responsible for its outputs. That sounds a strange thing to say but Paul Jennings at Rolls-Royce always used to remind me You can’t work on outcomes.

The difficulty that the Amagasaki train drivers had was that the railway was inherently subject to sources of variation over which the drivers had no control. In the face of those sources of variation, they were pressured to maintain the discipline of a punctual timetable. They way they did that was to transgress other dimensions of process discipline, in the Amagasaki case, speed limits.

Anybody at work must diligently follow the process given to them. But if that process does not deliver the intended outcome then that is the responsibility of the manager who owns the process, not the worker. When a worker, with the best of intentions, seeks independently to modify the process, they are in a poor position, constrained as they are by their own bounded rationality. They will inevitably by trapped by System 1 thinking.

Of course, it is great when workers can get involved with the manager’s efforts to align the voice of the process with the voice of the customer. However, the experimentation stops when they start operating the process live.

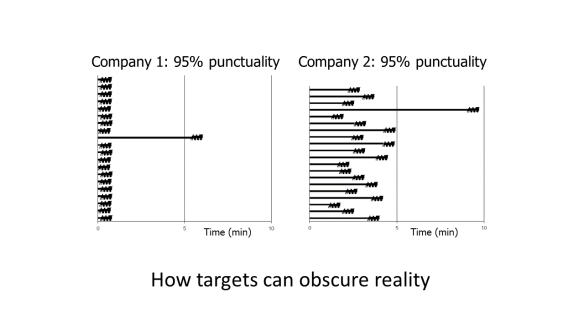

Fundamentally, it is a moral certainty that purblind pursuit of a target will lead to over-adjustment by the worker, what Deming called “tampering”. That in turn leads to increased costs, aggravated risk and vitiated consumer satisfaction.