… is a question I often get asked. I blog here about statistics, data, quality, data quality, productivity, management and leadership. And evidence. I do it from my perspective as a practising lawyer and some people find that odd. Yet it turns out that the collaboration between law and quantitative management science is a venerable one.

… is a question I often get asked. I blog here about statistics, data, quality, data quality, productivity, management and leadership. And evidence. I do it from my perspective as a practising lawyer and some people find that odd. Yet it turns out that the collaboration between law and quantitative management science is a venerable one.

The grandfather of scientific management is surely Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915). Taylor introduced the idea of scientific study of work tasks, using data and quantitative methods to redesign and control business processes.

Yet one of Taylorism’s most effective champions was a lawyer, Louis Brandeis (1856-1941). In fact, it was Brandeis who coined the term scientific management.

Taylor

Taylor was a production engineer who advocated a four stage strategy for productivity improvement.

- Replace rule-of-thumb work methods with methods based on a scientific study of the tasks.

- Scientifically select, train, and develop each employee rather than passively leaving them to train themselves.

- Provide “Detailed instruction and supervision of each worker in the performance of that worker’s discrete task”.1

- Divide work nearly equally between managers and workers, so that the managers apply scientific management principles to planning the work and the workers actually perform the tasks.

Points (3) and (4) tend to jar with millennial attitudes towards engagement and collaborative work. Conservative political scientist Francis Fukuyama criticised Taylor’s approach as “[epitomising] the carrying of the low-trust, rule based factory system to its logical conclusion”.2 I have blogged many times on here about the importance of trust.

However, (1) and (2) provided the catalyst for pretty much all subsequent management science from W Edwards Deming, Elton Mayo, and Taiichi Ohno through to Six Sigma and Lean. Subsequent thinking has centred around creating trust in the workplace as inseparable from (1) and (2). Peter Drucker called Taylor the “Isaac Newton (or perhaps the Archimedes) of the science of work”.

Taylor claimed substantial successes with his redesign of work processes based on the evidence he had gathered, avant la lettre, in the gemba. His most cogent lesson was to exhort managers to direct their attention to where value was created rather than to confine their horizons to monthly accounts and executive summaries.

Of course, Taylor was long dead before modern business analytics began with Walter Shewhart in 1924. There is more than a whiff of the #executivetimeseries about some of Taylor’s work. Once management had Measurement System Analysis and the Shewhart chart there would no longer be any hiding place for groundless claims to non-existent improvements.

Brandeis

Brandeis practised as a lawyer in the US from 1878 until he was appointed a Justice of the Supreme Court in 1916. Brandeis’ principles as a commercial lawyer were, “first, that he would never have to deal with intermediaries, but only with the person in charge…[and] second, that he must be permitted to offer advice on any and all aspects of the firm’s affairs”. Brandies was trenchant about the benefits of a coherent commitment to business quality. He also believed that these things were achieved, not by chance, but by the application of policy deployment.

Errors are prevented instead of being corrected. The terrible waste of delays and accidents is avoided. Calculation is substituted for guess; demonstration for opinion.

Brandeis clearly had a healthy distaste for muda.3 Moreover, he was making a land grab for the disputed high ground that these days often earns the vague and fluffy label strategy.

The Eastern Rate Case

The worlds of Taylor and Brandeis embraced in the Eastern Rate Case of 1910. The Eastern Railroad Company had applied to the Interstate Commerce Commission (“the ICC”) arguing that their cost base had inflated and that an increase in their carriage rates was necessary to sustain the business. The ICC was the then regulator of those utilities that had a monopoly element. Brandeis by this time had taken on the role of the People’s Lawyer, acting pro bono in whatever he deemed to be the public interest.

Brandeis opposed the rate increase arguing that the escalation in Eastern’s cost base was the result of management failure, not an inevitable consequence of market conditions. The cost of a monopoly’s ineffective governance should, he submitted, not be born by the public, nor yet by the workers. In court Brandeis was asked what Eastern should do and he advocated scientific management. That is where and when the term was coined.4

Taylor-Brandeis

The insight that profit cannot simply be wished into being by the fiat of cost plus, a fortiori of the hourly rate, is the Milvian bridge to lean.

But everyone wants to occupy the commanding heights of an integrated policy nurturing quality, product development, regulatory compliance, organisational development and the economic exploitation of customer value. What’s so special about lawyers in the mix? I think we ought to remind ourselves that if lawyers know about anything then we know about evidence. And we just might know as much about it as the statisticians, the engineers and the enforcers. Here’s a tale that illustrates our value.

Thereza Imanishi-Kari was a postdoctoral researcher in molecular biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1986 a co-worker raised inconsistencies in Imanishi-Kari’s earlier published work that escalated into allegations that she had fabricated results to validate publicly funded research. Over the following decade, the allegations grew in seriousness, involving the US Congress, the Office of Scientific Integrity and the FBI. Imanishi-Kari was ultimately exonerated by a departmental appeal board constituted of an eminent molecular biologist and two lawyers. The board heard cross-examination of the relevant experts including those in statistics and document examination. It was that cross-examination that exposed the allegations as without foundation.5

Lawyers can make a real contribution to discovering how a business can be run successfully. But we have to live the change we want to be. The first objective is to bring management science to our own business.

The black-letter man may be the man of the present but the man of the future is the man of statistics and the master of economics.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1897

References

- Montgomery, D (1989) The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace, the State, and American Labor Activism, 1865-1925, Cambridge University Press, p250

- Fukuyama, F (1995) Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity, Free Press, p226

- Kraines, O (1960) “Brandeis’ philosophy of scientific management” The Western Political Quarterly 13(1), 201

- Freedman, L (2013) Strategy: A History, Oxford University Press, pp464-465

- Kevles, D J (1998) The Baltimore Case: A Trial of Politics, Science and Character, Norton

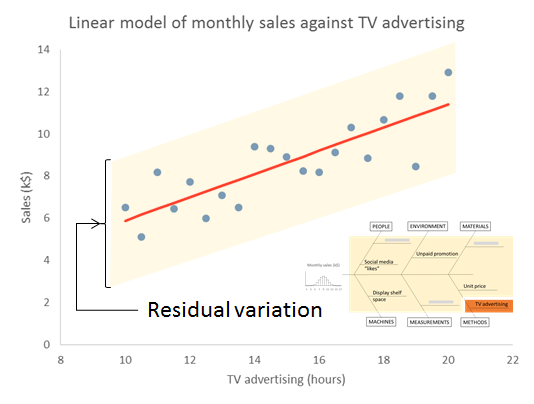

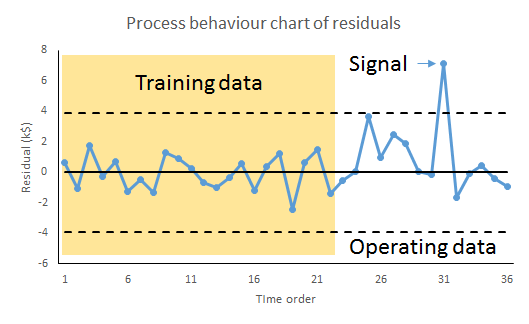

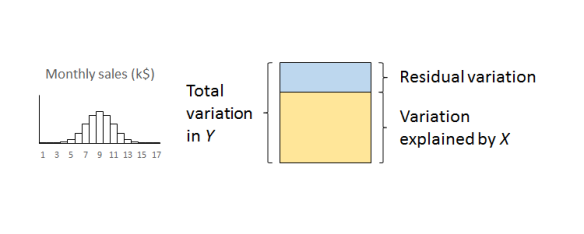

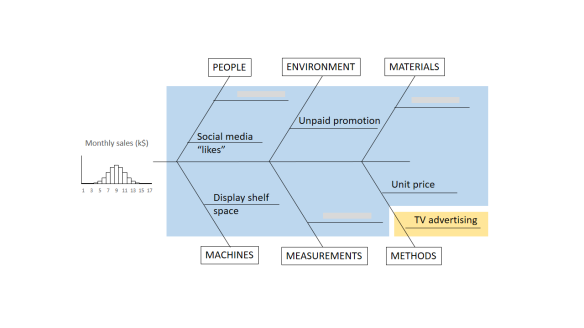

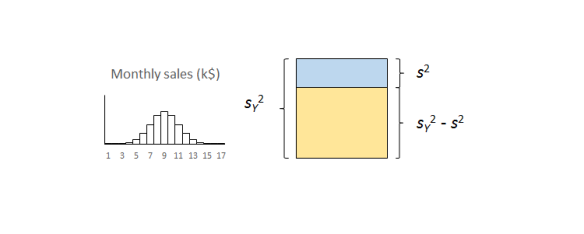

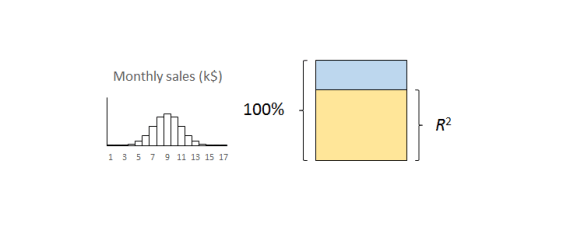

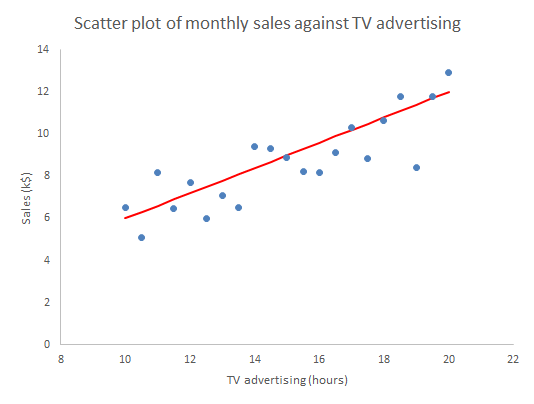

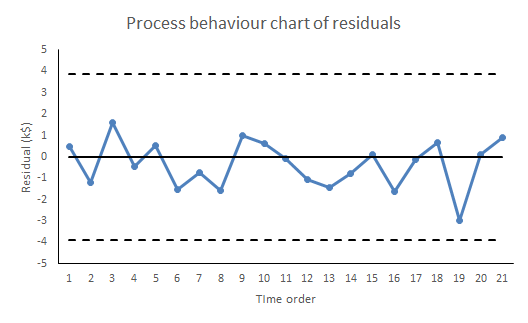

The important thing to remember is that the residual variation is not a statistical artifact of the analysis. It is part of the real world business system, the cause-system of the Ys.7 It is the part on which you still have little quantitative grasp and which continues to hurt you. Returning to the cause and effect diagram, we picked one factor X to investigate and took its influence out of the data. The residual variation is the variation arising from the aggregate of all the other causes.

The important thing to remember is that the residual variation is not a statistical artifact of the analysis. It is part of the real world business system, the cause-system of the Ys.7 It is the part on which you still have little quantitative grasp and which continues to hurt you. Returning to the cause and effect diagram, we picked one factor X to investigate and took its influence out of the data. The residual variation is the variation arising from the aggregate of all the other causes.

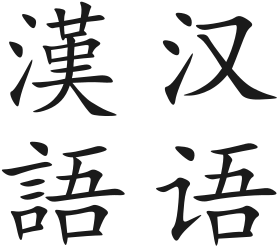

Between 1958 and 1960, 67 of the 120 inhabitants of the Chinese village of Xiaogang starved to death. But

Between 1958 and 1960, 67 of the 120 inhabitants of the Chinese village of Xiaogang starved to death. But